Thirty years later, in the preface to a 1993 revised edition of her 1969 book My Life with Martin Luther King, Jr., Coretta Scott King reflected on the disenchantment of many young people at the time with what they concluded was the failure of the Civil Rights movement to accomplish results that endured.

“…we also need to remember that the struggle is a never-ending process. Freedom is never really won. You earn it and win it in every generation. That is what we have not taught young people, or older ones for that matter. You finally win a state of freedom that is protected forever. It doesn’t work that way.”

I learned of this quote through my association with the Coretta Scott King Center for Cultural and Intellectual Freedom on the campus of Antioch College where I teach History. Coretta Scott attended Antioch, with her older sister Edythe, in the 1940s. At Antioch, Coretta Scott continued to develop her singing skills under the guidance of Walter Anderson, Antioch’s first Black professor. She was active in local cultural life as well as activism on campus and off. But she was unable to work as a student teacher in the Yellow Springs school district because, although the school system had been desegregated in 1887, when the Ohio legislature passed a law requiring it, no Black teachers had been hired by the system since then. Coretta Scott left Antioch before graduating and received her degree from the New England Conservatory of Music. In Boston she met Martin Luther King, Jr. and they married in 1953.

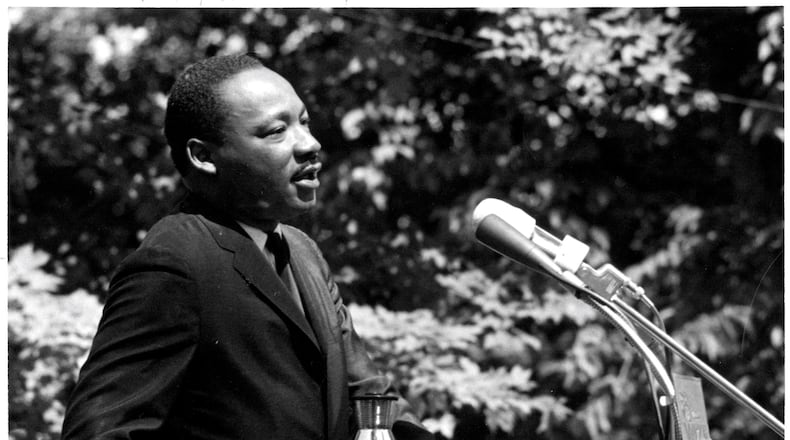

King: A Life, a 2023 biography by Jonathan Eig, reminds us of how unpopular King was during his life because of the “trouble” he was making, but also of the important role that his wife Coretta Scott King played in his life, and in the civil rights movement. She was a homemaker, helping to raise their four children, but she also joined some protests, and she continued to advise him and be a sounding board on issues related to the movement.

The two related quotes above, from this activist couple, came to mind as I reflect on celebrating the Martin Luther King, Jr. holiday in our current moment. The worldwide Black Lives Matter protests that followed the May 2020 murder of George Floyd were called a “racial reckoning,” suggesting that they would be followed by lasting change. Large corporations and some wealthy individuals made commitments to invest in diversity, equity, and inclusion programs moving forward. One goal of these programs is to address systemic racism, racism that is threaded in our laws and practices, something that both Kings experienced growing up in the segregated south.

In the summer of 2020 conservative journalist Christopher Rufo began leading a very successful media campaign to distort the goals of critical race theory, the analytical framework developed in the 1970s to understand and begin challenging systemic racism. Having successfully confused the general public about the meaning of critical race theory, Rufo expanded his media campaign to distort the purposes of diversity, equity, and inclusion programs. Most recently, he has gained the support of billionaire investor William Ackman, who leveraged his wealth to play an important role in critiquing Harvard President Claudine Gay. After her ouster at the beginning of this year, Ackman noted that he is just beginning his attack on diversity, equity and inclusion programs on college campuses, claiming that they promote racism and inequality, adopting Christopher Rufo’s claims. A demand for change was made, equity in hiring, and those in power are resisting it by distorting the meaning of the demand, the purpose of diversity, equity and inclusion programs. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Coretta Scott King would expect a strategic response, which I hope community organizers and media professionals committed to justice are developing.

Coretta Scott King reconciled with Antioch College. In 1965 she returned to the campus when Martin Luther King was the commencement speaker. She came back again in 1967 when the college awarded her with the degree that she had abandoned. Antioch had concluded that at the time she left the college, Coretta Scott had met all the requirements for graduation. The final time she visited Antioch College was in June of 2004 to receive the Horace Mann Award given to alumni who have provided exemplary civil service. In her remarks, profiled in this newspaper, reporter Shareen Samavati explained that King noted that “diversity isn’t only about having a diverse student body; it’s about students and faculty of varied religions, races and ages being respected on campus.” Understanding the good trouble that had led to more diverse campuses, she stated that “a university should look like America.” A message for today.

Kevin McGruder, M.B.A., Ph.D. is Associate Professor of History at Antioch College; information on The Coretta Scott King Center is available at antiochcollege.edu/coretta-scott-king-center

About the Author